Democratic Constitutions Against Democratization

Law and Administrative Reforms in Weimar Germany and Implications for New Democracies

Kyong Jun Choi – The Korean Journal of International Studies 17-1 (April 2019), 31-53

- Abstract

- This study discusses the importance of bureaucracy in a state’s initial period of democratization. By examining the case of the Weimar Republic, this study argues that democratic constitutions and judicial independence can create a paradoxical situation wherein democracy itself permits the development of anti-democratic sentiment and action within state institutions. The democratic constitution of the Weimar Republic restrained the regime’s efforts to reform the undemocratic institutions of the state and eventually had a detrimental effect on the stability of the democratic regime and the consolidation of democracy. In the case of uneven democratization across the electoral, administrative and legal systems of the state—a situation quite common in newly democratic countries—democratic constitutions can actually function against democracy by guaranteeing the legal and political rights of anti-democratic forces within the state. This can further perpetuate the uneven democratization of state institutions and may eventually threaten the stability and viability of the newly established democratic regime itself. The German case provides current newly democratic states with the lesson that a democratic regime must protect itself against internal threats seeking to use the safeguards of the constitution to destroy the system itself.

- Keywords : democracy, constitution, administrative reform, Weimar Germany, new democracies

- Introduction

- What is the role of the law and constitutions in the consolidation of democracy? Are democratic constitutions always beneficial to democracy? This study investigates the paradoxical effect of a democratic constitution on the consolidation of democracy in a newly established democratic state. Specifically, the administrative reforms of the German Weimar Republic (1919–1933) illustrate the ways in which a democratic constitution can be detrimental to the stability of a new democratic regime, and eventually, to the consolidation of democracy. By investigating the constraining effects of democratic constitutions on political leaders’ efforts to reform public administration and legal systems, this study argues that a democratic constitution can negatively affect the viability of a democratic regime and the consolidation of democracy in a new democratic state.

The German Revolution of 1918 marked the end of the Second Reich and the beginning of the transition to the Weimar Republic. This period of dramatic regime change provides a valuable case study of the effect of a democratic constitution on the beginning stages of democratization. The new democratic elites (i.e., the socialists and their coalitions) inherited a bureaucracy and judiciary that had traditionally been dominated by certain social classes—in particular, the so-called Junker class, comprising the Prussian landed nobility— who were anti-democratic and anti-republican, and who had little interest in establishing a stable alliance with the new political regime. The Weimar leadership attempted to restructure the legal parameters of the political system to imbue the new bureaucracy with a democratic ethos by giving the bureaucrats political and civil rights (Wilson 1993, 430). However, this effort ultimately had unintended negative consequences. The rights given by the new constitution to the bureaucrats, which were given even to those who were recruited during the authoritarian regime and who maintained an anti-democratic ethos, restrained administrative reform, and encouraged political activity among the bureaucrats, which destabilized the regime. In other words, instead of consolidating the process of democratization, granting generous civil service rights to the bureaucracy weakened the democratic regime and helped the civil service fight against the democratic republic itself (Marx 1934, 47; Glees 1974, 826).

This study uses the case of the Weimar Republic to illustrate the importance of the class-embeddedness of the administrative and legal bodies of the state, and the uneven democratization of divergent state institutions as negative conditions for the consolidation of democracy. Although Germany accomplished abrupt electoral democratization after the collapse of the Second Reich, public officials and judges remained the most powerful opponents of the new democratic state (Orlow 1986, 123). While the democratization of institutional electoral bodies (particularly the German parliamentary system) accelerated, that of administrative and legal bodies lagged, due in large part to the influence of the anti-democratic classes. Paradoxically, the democratic constitution of the Weimar Republic restrained the regime’s efforts to reform these undemocratic institutions. In cases of uneven democratization across the electoral, administrative, and legal systems of the state (a situation quite common in newly democratic countries), a democratic constitution can actually work against democracy by guaranteeing the legal and political rights of antidemocratic forces within the state. This situation can further perpetuate the uneven democratization of state institutions, and may eventually threaten the stability and viability of the newly established democratic regime itself.

This study does not argue that democratic constitutions are always or essentially detrimental to democratization. Instead, it argues that under conditions specific to the initial stages of democratization, a democratic constitution can negatively affect the democratization process as a whole, particularly in a political system in which (1) the bureaucracy and judiciary are controlled by conservative (anti-democratic) groups or classes, and (2) the constitution protects the legal and political rights of those anti-democratic forces within the state. During the initial stages of democratization, judicial independence can be detrimental to this process, and political control over the administrative bodies and courts may be necessary to protect the process of democratic consolidation.

- THEORIES OF DEMOCRATIZATION AND JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE

-

DESIGNING DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTIONS IN NEW DEMOCRACIES

Numerous studies have attempted to explain how and why certain countries have achieved significant democratization, while other countries have experienced only the perpetuation of dictatorship or the repetition of temporary democratization and backlashes (Moore Jr. 1966; Huntington 1968; Linz and Stepan 1996; Fish 2001; Bermeo 2016). Among many factors that negatively affect democratic consolidation in developing countries, the most pressing problem has been ensuring the political stability of the new regime and institutionalizing the political order in the process of democratization. Throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America, a decline in political order and an undermining of the authority, effectiveness, and legitimacy of government have been common situations encountered by new democracies. In these areas, the political order is a goal, not a reality (Huntington 1968, 4).

Designing a democratic constitution as an element of an institutional framework that supports stable democratic rule is critical in new democracies, which face weak political order and undermined authority. Studying constitutions and law has contributed to understanding the problems of countries that design democratic legal and institutional frameworks to attempt democratization, and eventually, democratic consolidation after the abrupt collapse of authoritarian regimes or liberation from colonial rule. Previous comparative studies in the realm of law and politics have focused on the formation and evolution of democratic legal systems and institutions, such as independent judiciaries (Moustafa 2003; Tiede 2006; Hirschl 2008; Helmke and Rosenbluth 2009; Woods 2009).

Such research investigates the conditions necessary for judicialization and illustrates how independent judiciary and democratic legal systems support political democratization and the consolidation of democracy. As a third party, an independent and objective judiciary, which is able to impose meaningful restraints on the state and individual members of the ruling elite, is critical to establishing and maintaining democratic legitimacy. By helping secure the legitimacy of the regime, independent judiciaries can increase the stability and viability of the newly established democracy. An independent and effective judiciary, or a court with the power of judicial review, has been considered a crucial element of establishing the rule of law in new democracies (Ginsburg 2003; Peerenboom 2004). Judicial independence, in this case, is the judiciary’s independence from the influence of the executive branch; the judiciary is not considered independent when the executive branch or its agents, such as the ministry of justice, exert significant control over the judiciary, its resources, or the judges themselves (Tiede 2006, 133–34).

The importance of the independence of the judiciary from the executive branch has been emphasized by scholars in the political science field, because authoritarianism can make authoritarian governance more durable by concealing anti-democratic practices under the mask of law and perpetuate their power through the same legal mechanisms that exist in a democratic regime, including the judiciary (Varol 2015). The legal use of democratic institutions or the rule by law can undermine democracy, and cause democratic backsliding, rather than leading to the entrenchment of democracy (Magaloni 2008, 181; Chu and Im 2013, 119).

Despite the insight provided by previous research into the role of judicial independence in democratization, few studies have discussed the embeddedness of judiciaries in a larger system of social class control. By focusing on judicial independence from the executive branch, the existing literature has largely ignored the importance of judicial independence from social forces, such as class. In countries in which the majority of judges are recruited from a certain social class, or are controlled by a certain social group, independence from the executive branch cannot guarantee the true independence or objectivity of the judiciary (Thompson 1975, 265). Furthermore, when the court is controlled by anti-democratic social forces, its independence from the control of democratically elected politicians can threaten the viability and stability of the democratic regime itself.

This situation raises the importance of democratic self-defense in new democracies, where the survival of democracy is often threatened by those who seek its demise (Kirshner 2014). Democracy needs to assert itself through various defensive measures against those anti-democratic forces for the selfdefense of democracy (Malkopoulou and Norman 2018). Those anti-democratic forces can exist not only in society as a form of political movement aiming to dismantle democratic institutions but also in state institutions as bureaucrats and judges protected by democratic laws and constitutions.THE RABBIT ON THE TURTLE’S BACK: UNEVEN DEMOCRATIZATION IN THE STATE

One of the critical elements of democratic consolidation is securing an autonomous and impartial state officialdom, or a “bureaucracy that begins to operate in an impersonal manner, according to known rules and regulations, and in which the officials are able (or obliged) to separate their own political and personal interests from the offices they occupy” (Suleiman 1999, 144). However, a problem for the leadership of a new democratic regime replacing an authoritarian predecessor is that this ideal bureaucracy does not exist in the transitional period. On the contrary, the democratic elites must construct a democratic system from the wreckage of a destroyed state system, as in post-Soviet Russia, or struggle with a firmly established bureaucracy “previously operated under different guidelines, ethics, and ideology,” as in the Weimar Republic (Suleiman 1999, 145).

The key problem for unconsolidated democracies is the inability to recruit a critical mass of dependable officials to administer democratic institutions and implement the policies and plans established by the political leaders (Hanson 2001, 128, 141). However, these leaders are in a paradoxical situation of “overcoming the inheritance of the past given the impossibility of replacing the civil service overnight” (Baker 2002, 9). State officials cannot be replaced overnight not only because a country’s civil service is a product of its culture, history, and political ideology but also because producing efficient bureaucrats requires resources and time for training, and because the abrupt replacement of disloyal, experienced bureaucrats with loyal amateurs causes instability and inefficiency in state apparatuses (Baker 2002, 7–8; Barabashev et al. 2009, 295–96).

Therefore, the new political leaders are confronted with the paradoxical problem of delivering a representative democratic program by means of a civil service that functioned under authoritarianism. These political leaders must not only struggle with but also rely on the bureaucracy (Geddes 1994, 182–84). This dilemma of a state in transition reveals the importance of the norms, values, and political ideologies held by bureaucrats. Under the transition conditions, state service reform must introduce methods of management and create new statuses for officials completely different from those of the old regime. However, if the new democratic regime focuses only on the structures and functions of the state without paying attention to the mentality or worldview of the officials themselves, the new regime will achieve only a cosmetically altered officialdom, and will maintain the ethos and behavior patterns of the previous bureaucracy. A reform of officialdom during a transition in the form of rule cannot be a purely technical exercise; the reform requires clarity concerning the new values to be introduced (Barabashev et al. 2009 2009, 295–96).

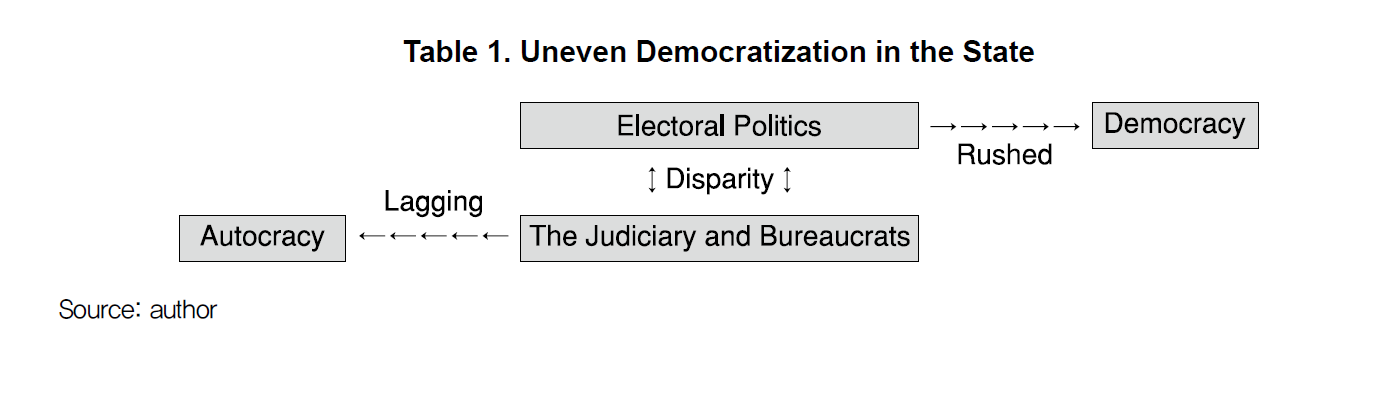

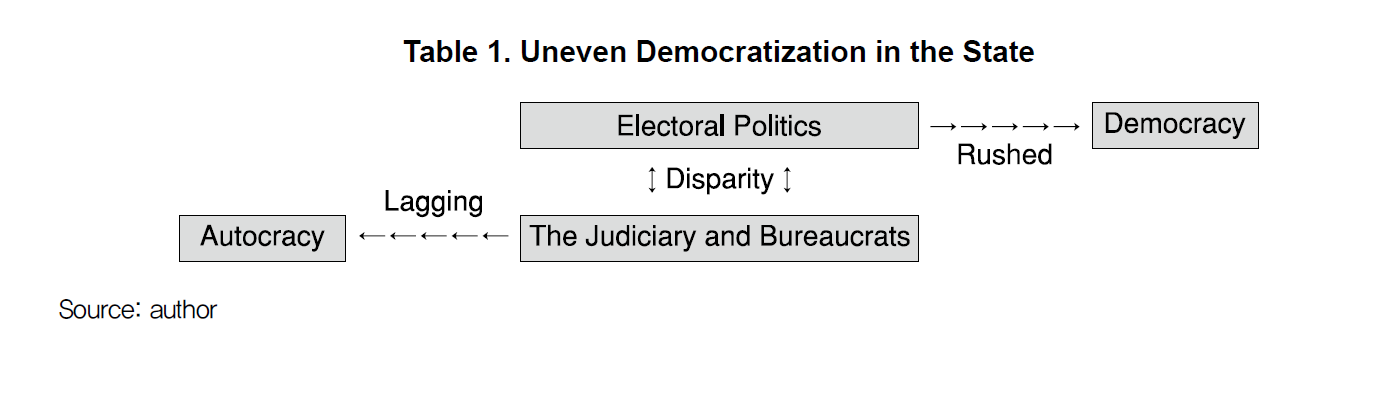

Theories of democratic transition and legal studies of judicial independence must consider the specific conditions that a newly established democratic regime encounters in the initial stages of the democratic transition. Although many newly democratic countries accomplish democratization in their electoral institutions, other institutional bodies of the state, such as the administrative and judicial bodies, in many cases retain the non-democratic and antirepublican forces of previous authoritarian regimes. In this condition of uneven democratization, democratic constitutions, which protect the political voices and civil rights of anti-government forces within the state, can be detrimental to the completion of democratic transition and consolidation of democracy. Table 1 illustrates the disparity in democratization speed between electoral and bureaucratic institutions (i.e., the rabbit on the turtle’s back).

The potential negative effect of a democratic constitution in a newly democratic country is examined through the case of Weimar Germany, which nicely illustrates how bureaucrats and judges who either are controlled by or collaborate with anti-democratic forces can negatively affect the process of democratization. The democratic constitution established by the Weimar Republic paradoxically guaranteed political rights and institutional independence to bureaucrats and judges who were themselves among the strongest opponents of the democratic regime. The disparity between the democratization speeds of the electoral and bureaucratic institutions—in other words, the rushing rabbit on the back of the lagging turtle—detrimentally impacted the fate of the Weimar Republic.

- CONSTITUTIONS AND ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS IN WEIMAR GERMANY

- One of the main problems for the leaders of the Weimar Republic, who abruptly came to power with Germany’s defeat in the First World War, was converting the existing bureaucratic organizations into pro-democratic and pro-republic entities. This transition involved balancing two conflicting values: bureaucratic efficiency and loyalty to the new democratic regime (Fried 1943; Jane 1988). However, a strong, efficient bureaucracy that remained loyal to the previous regime hindered these efforts. Under the Kaiserreich and the preceding Prussian regime, bureaucrats had been recruited largely from the Junker social class, the members of whom shared the social background, economic interest, and political ideologies with the old regime (Muncy 1970; Vierhaus 1999). The issues of how to deal with this strong and cohesive conservative bureaucracy and how to balance efficiency and loyalty were crucial to the fate of the Weimar Republic democracy.

EMBEDDED BUREAUCRACY AND JUDICIARIES

German bureaucracy, especially the Prussian bureaucracy of the absolute monarchy and the Second Reich, is considered a forerunner of the modern professional public service (Wollmann 1989, 234). The bureaucracy’s dedication and efficiency were not only highly regarded by German but also were looked upon by foreign observers as “Germany’s greatest contribution in the field of political organization and as an encouraging example for the whole world” (Marx 1934, 467–68). The founders of the absolute monarchy in Germany invented effective instruments of administration, which became the foundation of a thoroughly bureaucratized state (Rosenberg 1958, 13).

The strength of the German bureaucracy—that is, its efficiency, cohesiveness, and reliability—was derived primarily from a recruitment pattern structured by triangular relations among politicians, bureaucrats, and dominant social forces. The Junkers, originally comprising the land-owning nobility of East Prussia, dominated German–Prussian officialdom, and formed a stable alliance with the political elites that lasted through the end of the Second Reich (Vierhaus 1999, 151). The Junkers’ tradition of educating members in the military and bureaucracy made them loyal supporters of the monarchy, and Prussian absolutism was characterized by the privileged integration of the Junker nobility into royal service in the military and the civil service. Through the integration of the nobility into the state service and the development of a professional bureaucracy, an alliance of interests emerged between the Junkers and the senior officials of the state. These were, of course, conservative forces that held vested interests in the monarchical system and were loyal to the Prussian king who was granted the title of German emperor (Muncy 1970, 34, 37; Vierhaus 1999, 159).

Of course, the Prussian administration was not perfectly monopolized by the Junker class as other (non-Junker) nobles and commoners also assumed considerable responsibility in Prussian officialdom. However, the importance of the Junkers in the formation of bureaucratic characteristics in Germany cannot be overstated; they played a crucial role in central Prussian administration, as well as regionally in provincial and government districts, and in the local Circles of the Prussian state system (Muncy 1970, 140–41, 160–70, 203–10).

In particular, the post of the Landräte (the county directors) held special importance for the Junkers’ influence in the community and their careers as bureaucrats. It was said that the government’s power reached only as far as the Landräte, which were the hinge between the central government and communal self-administration. The Landräte chaired county council meetings, sat in the council as the king’s representative, supervised the performance of all police functions, conducted all elections in the county, and collected all direct taxes; therefore, it was impossible for the average burgher to avoid encountering the Landräte in public life (Witt 1985, 140–41).

During the Second Reich, the government continued to seek civil servants from among the nobility, particularly the Junkers, who enthusiastically supported the monarchy. Conversely, Social Democrats and even the sons of Social Democrats were automatically excluded from the bureaucracy. Because a long training period and extensive education were necessary for entry into the senior civil service, factory workers and others were provided little opportunity to secure a place in the civil administration (Rohl 1967, 7–8). Only one who had demonstrated his undivided loyalty to the existing political system could expect permanent incorporation into the civil service of Prussia and the Second Reich, and reap the resulting financial and social privileges (Witt 1985, 138–39).

The civil service proved to be a valuable ally in the government’s struggle to retain monopolistic control over the administration. Most candidates for civil service internalized the values promoted by the monarchy. They found themselves in “an iron net of conservative administration and selfadministration,” and believed a liberal government was impossible (Jacob 1963, 63–64). German officials played a particularly powerful role within the framework of the monarchy, thus gaining a special social reputation and developing a strong caste mentality in the process (Vierhaus 1999, 152).

The Junkers managed to survive as a privileged ruling stratum into the twentieth century by preserving their dominance of Prussia’s state officialdom and influential political and administrative positions. Their backward-looking status as a privileged ruling class and attempt to cling to social and political inequality, as well as economic supremacy, resulted in tensions and conflict that eventually prevented their integration into the Weimar Republic and constructive participation in the consolidation of the improvised parliamentary democracy. The Junker class eventually played an important and catastrophic role in determining the fate of democracy in the Weimar Republic by acting as co-directors of the destruction of parliamentary democracy and helping restore an authoritarian form of government. After the collapse of the republic, the Junkers became beneficiaries and tools of the Third Reich (Rosenberg 1985, 83, 107–8).

Judges under the Second Reich also enjoyed significant social prestige. They came from middle- and upper-middle-class backgrounds, and enjoyed the prestige of inclusion in the small stratum of university-trained professionals in German society. Judges were clearly members of the elite class, although judicial offices did not offer as much social prestige as administrative posts, and the highest judges had no governing powers. More importantly, judges were politically conservative, nationalistic, and vehemently anti-socialist and anti-Semitic. Although they had an independent position supported by their theory of jurisprudence, their values did not conflict with those of the emperor and the aristocracy. Under the monarchy, the judiciary played the role of extending the executive power and legitimacy of the existing regime. Although the judiciary was institutionally independent from the executive branch, especially when compared to other administrative positions, judges nevertheless maintained a strong political orientation toward the interests of the aristocracy, and thus, served as a bulwark of systemic stability. Therefore, the judges represented a defender protecting the status quo not only in the Second Reich but also later in Weimar Germany (Muncy 1944, 71; Bookbinder 1996, 112).

This internally cohesive, strong bureaucracy that was loyal to the emperor and was embedded in dominant social forces was problematic for the new democratic elites of the Weimar Republic—that is, the socialist politicians of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), who did not share the socioeconomic background and ideological orientations of the bureaucrats. The bureaucracy considered the SPD internal opponents of the German empire. In 1903, the Bavarian ambassador reported that “a Chancellor who wished to work with a Liberal majority in the Reichstag would have to begin by re-staffing the entire Prussian provincial administration, since the Landräte and Regierungs Präsidenten (heads of regional governments) would refuse to carry out a policy to which they were opposed” (Rohl 1967, 116). The political leaders of Weimar Germany had to choose between the efficiency of the existing bureaucracy and the loyalty of the new bureaucracy to the new regime.LEGAL AND BUREAUCRATIC REFORMS IN THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC

The dramatic regime change from the Second Reich to the Weimar Republic offers an opportunity to observe the interactions between bureaucracies and counter-elites. The demise of the Second Reich resulted in the ascendance of the socialists, previously regarded as internal opponents, or even enemies, of the state (Wilson 1993, 430).

The pressing problem faced by the Social Democrats was that they lacked the experience and training necessary to take over state administration from the bureaucrats. However, if democratic programs were to be reliably implemented, the old bureaucrats had to be replaced with new, loyal administrators with democratic values. Nevertheless, the new regime was concerned that purging the existing civil servants might engender an administrative vacuum, because efficient bureaucrats cannot be produced overnight. Furthermore, the Weimar regime was not only confronted with the challenging duties of economic recovery from the defeat of war but also threatened by the extreme left (i.e., the communists) who tried to overthrow the republic from the beginning, which intensified the demand for a stable and efficient bureaucracy (Muncy 1973, 488– 89).

The SPD leadership’s priority was to stabilize a defeated and disordered nation, and Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the SPD who became the first president of the republic in 1919, was particularly convinced that this was impossible without the collaboration of the existing administration. He welcomed the collapse of the Second Reich with the words, “I hate revolution as I hate sin” (Fried 1943, 505). When the Constitutional Convention assembled in Weimar, the bureaucrats found themselves courted by nearly all the political groups, who were united in their desire for quick reconstruction of the Reich, and surrounded by the “cannon muzzles of a hostile world of communist uprisings” (Marx 1934, 469). Democratizing the bureaucracy and taking steps to ensure that it was organized and staffed in such a way that administrators would support rather than sabotage the democratic system should have been high on the agenda of the revolutionary and early parliament cabinets. The ministries’ failure to act decisively in this area undermined the viability of the new government in its early days (Muncy 1973, 487–88).

The Weimar leadership did take steps to restructure the bureaucratic system, notably by restructuring the legal–institutional framework of the bureaucracy to introduce democratic values, and by changing the patterns of recruitment, which had previously been the province of the now-hostile Prussian and German social elite. The reformers made changes in the organizational structure of the government and introduced measures of a new personnel policy to recruit men imbued with the new democratic-republican spirit, such as the abolition of technical qualifications for appointment, and thus, opened some public servant posts to a wider pool of formally untrained candidates (Seabury 1954, 15; Frank 1966, 731–32; Caplan 1988, 42).

However, the bureaucrats’ rights accorded by the new constitution in Weimar Germany made it difficult to purge anti-democratic bureaucrats from the government and judges from the court. Paradoxically, by encouraging political activity among the bureaucrats, these rights destabilized the bureaucratic system, which contributed to the regime’s instability.

First, the constitution made it difficult to purge anti-republican elements from the civil service. Article 129 declares that “[c]ivil servants are appointed for life unless other provision is made by law” and that “[t]he duly acquired rights of civil servants are inviolable” (Blachly and Oatman 1928, 667). Not only were German civil servants guaranteed lifetime tenure, but their suspension, transfer, and retirement were also strictly regulated by law. Second, when these clauses regarding the job stability of civil servants were combined with Article 130 of the Constitution, which allowed “freedom of political opinion and freedom of association” (Blachly and Oatman 1928, 668), expelling civil servants from their posts on the grounds of political orientation, whether anti-democratic or antirepublic, became legally impossible.

Consequently, “[u]p to 1924, state policy was to be caught in the political contradictions of meeting democratic pressure for a purge of anti-republican elements from the civil service, while at the same time trying to maintain the constitutional commitment to civil rights of civil servants” (Caplan 1988, 28). In other words, the Weimar leaders were ensnared in the paradox that democracy gave freedom and rights to anti-democratic forces. Ironically, the democratic ideas, policies, and rules of the Weimar Republic were intended to be bolstered and embodied by a state apparatus imbued with an anti-democratic ethos.

Further, the constitution legally paved the way for the politicization of civil servants. The provisions of Article 130 violated the political neutrality of civil servants by promoting their political activity. Article 130 is, in fact, ambiguous and contradictory. It declares: “Civil servants are servants of the entire public, not of a party.” However, it also declares: “All civil servants are guaranteed freedom of political opinion and freedom of association” (Blachly and Oatman 1928, 668). In other words, “while the first sentence [of Article 130] clearly suggested that political neutrality would be expected of civil servants, the second, with equal clarity, promised them wide freedom of political behavior” (Caplan 1988, 25–26). In 1919, the national government assumed the position that officials were bound to serve the republic faithfully only while carrying out their official duties. Outside official duties, officials were free to seek the constitution’s abolition as long as they did not resort to force (Showalter 1983, 107).

Moreover, the constitution bestowed upon bureaucrats not only the privilege of free party affiliation but also the right to be members of the Reichstag (Diet) or a Landtag (State Diet), while still maintaining their official duties according to Article 39, which declared that “[p]ublic officers and members of the armed forces need no leave in order to perform their official duties as members of the Reichstag or of a Landtag. If they are candidates for a seat in these bodies, they are to be granted the requisite leave to prepare for their election” (Blachly and Oatman 1928, 650). Weimar civil servants, unlike their predecessors, were permitted to become active political party members, and even stand for election without prejudicing their official status (Seabury 1954, 14). The Weimar Constitution did not even consider the problem of the anti-constitutional political parties that were rampant during this period.SELF-POLITICIZATION OF CIVIL SERVANTS AND THE JUDICIARY

The politicization of civil servants is generally taken to mean “the substitution of political criteria for merit-based criteria in the selection, retention, promotion, rewards, and disciplining of members of the public service” (Guy and Pierre 2004, 2). Attendant on this is the destruction of bureaucratic values. However, this definition of politicization does not appropriately apply to the politicization of Weimar bureaucrats. Because German civil servants were guaranteed job stability and freedom of political opinion and association, politicians could not easily control the civil service by arbitrarily appointing and promoting their preferred officials. Thus, the politicization of bureaucrats by political infiltration from above was not feasible under the terms of the new constitution. However, another kind of politicization occurred in Weimar Germany: the coalescing of civil servants into a political force independent of their political leaders, also known as self-politicization.

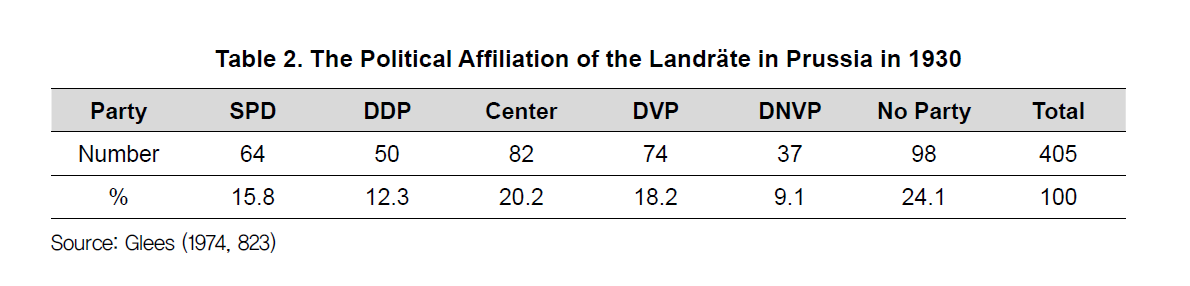

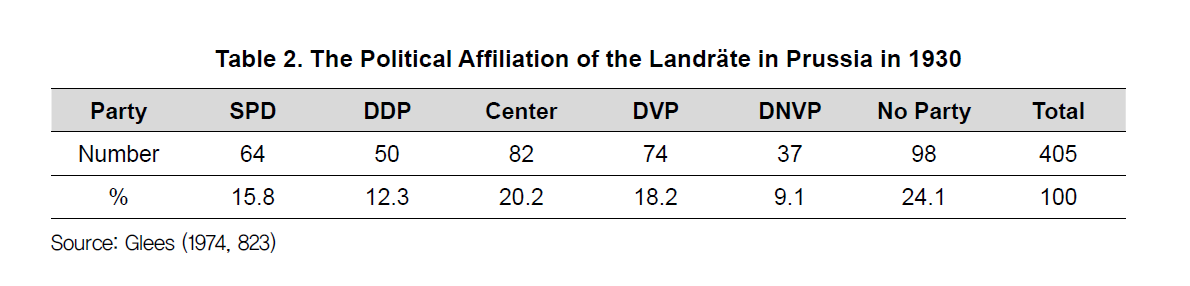

In 1919, only 20 of 423 (4.7 percent) Prussian Landräte claimed affiliation with the SPD. In 1925, 58 (14.5 percent) of 398 Landräte for whom data are available (of a total of 423) claimed to be affiliated with the Socialist Party, while 71 (17.8 percent) belonged to the Catholic Center Party, 22 (5.5 percent) to the Democratic Party (DDP), and 7 (1.7 percent) to the rightist German People’s Party (DVP). Thus, in 1925, about 37.5 percent of the Landräte openly acknowledged allegiance to one of the republican parties (Jacob 1963, 98). However, in 1930, 64 of 405 Landräte (15.8 percent) belonged to the SPD, while 27.3 percent openly supported right-wing parties, such as the DVP and the German People’s Nationalist Party (DNVP; Glees 1974, 823). Table 2 shows the political affiliation of the Landräte in 1930.

The politicization of civil servants was a threat to the democratic regime, particularly when the extreme political left (i.e., communists) and the extreme political right (i.e., Nazis) endangered the political stability of Germany. The generous granting of the right of freedom and association to the civil service was destined to weaken rather than strengthen the democratic polity because the unintentional result was that “the civil service was dragged closer to the arena of party politics” (Marx 1934, 471). As long as the government coalitions in Germany changed only within the “spiritual borderlines of Weimar ideology,” the politicization of the bureaucracy was merely a handicap. However, a complete shift of ideology could easily turn that handicap into a menace to the republic (Marx 1934, 473). It is significant that the anti-republican right-wing parties, which by then included the Nazi Party, recognized that “greater democratization of the civil service would help them in their fight against the republic” (Glees 1974, 826).

The legal–institutional framework of the Weimar Republic was not conducive to establishing a reliable bureaucracy loyal to the democratic regime. Mutual hostility had arisen between the leftist government and the civil servants. In the state of Thuringia, for instance, most state employees were holdovers from the ducal states, and the socialists made no secret of their distrust of the bureaucrats. Political friction between politicians and bureaucrats promoted severe bureaucratic disaffection (Tracey 1972, 207–8). In the Prussian state, it was not until after the shock of the March 1920 Kapp Putsch that the Weimar coalition parties agreed on the need to eliminate politically unreliable officials from the Prussian civil service and install those loyal to the parliamentary form of government (Orlow 1986, 132). However, the new regime continued to depend on some field officials appointed by the monarchy; in 1922, at least 36 percent of the Landräte in Prussia had been appointed before 1918 (Caplan 1988, 43).

Relations between politicians and anti-democratic judges also negatively impacted the stability of the democratic regime. When the republic was created, the new leaders did not move to reform the judiciary in accordance with republican principles, because the leaders were committed to liberal pluralism and believed that the judiciary should be independent and politically neutral (Bookbinder 1996, 112). In Prussia, for example, a decree on February 26, 1919 authorized the cabinet to remove political appointees who had not reached the customary retirement age of sixty-eight and permitted officials in this age category to apply for early retirement if they felt that remaining in office would create a conflict of conscience for them. However, in practice the decree remained dead letters and was seldom used. The minister of the interior and the cabinet rarely initiated mandatory retirement proceedings against politically suspect individuals. Most importantly, the original decree did not apply to judges and other members of the judiciary, because the majority of the cabinet felt that including them in the provision would endanger the non-political character of the judicial system. However, Prussian judges were among the most powerful opponents of the new democratic state, and these judicial personnel did not fall under the February 1919 decree until the Kapp Putsch (Orlow 1986, 124).

The judiciary passed legal decisions against the policies and programs of the government, and even against the Weimar Constitution. Whenever the fundamental rights provisions of the Weimar Constitution exceeded the civil rights that were guaranteed by existing law, the new rights were generally struck down by the courts. This was most apparent in the reactionary interpretation of an individual’s property rights, which refused to affirm the constitution’s commitment to the social responsibilities of ownership. In the area of nationalization, for example, the courts, for the most part, refused to recognize the principle of confiscation without compensation, although this was possible under the terms of the new constitution (Mommsen 1989, 59).

The decision not to reform the judiciary contributed substantially to undermining the new state. The judges became part of the opposition, and began to serve their own ideas of the proper form and role of the state. Creating a private law, they subverted the public law of the republic by refusing to administer justice equally to all people. In a sense, the judiciary assumed for itself the role of the state, and regarded the leaders of the Weimar government as illegitimate usurpers. Consequently, the administration of German justice during this period showed an extreme right-wing bias. These judges were the ultimate example of civil servants committed to their own view of the state and to the promotion of their own power at the expense of that of elected officials (Bookbinder 1996, 112–13, 117).

The politicization of the government branches extended to law enforcement agencies. The organizational ethos and political orientation of the police did not change into the ideal of the “people’s police” intended by the Social Democrats. The royal state police forces during the Second Reich maintained the image and prestige of the military, and almost all police officers at the time had been soldiers. With this military model, the image of the police as “aloof agents of the state rather than servants of the people” formed. The combative environment of Weimar Germany, in which the new police force encountered endless political struggles and uprisings by the extreme left and right, promoted a preference for veterans as police officers (Browder 1996, 20–21). The new police force of the Weimar Republic was organized along military lines, and the command structures mirrored those of the Prussian army. Police officers were recruited primarily from among Prussian army officers who had become jobless after the First World War (Reinke 1997, 95). All these political, conditional, organizational, and mental aspects of the police preserved and perpetuated a military ethos within the police force.

The Weimar Constitution, which, as illustrated above, provided full freedom of political rights and association to public servants, fostered a negative environment for forging democratically oriented police forces. As with many other contemporary public servants, the police of the Weimar period were unionized, and in Prussia, the police officers’ unions reflected the larger split of political orientation. The Schrader Verband, for example, which claimed to represent 70 percent of the rank and file, supported and encouraged government reforms to democratize the police. However, this movement generated a counterpart, the Verein der Polizeibeamten Preussens, which claimed to represent 90 percent of police officers, and fought for military and authoritarian traditions (Browder 1996, 21–22). These political expressions and rifts within the police damaged the image of the police as neutral, apolitical, objective law enforcers.

- DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTIONS AND UNEVEN DEMOCRATIZATION IN THE STATE

- The collapse of the Weimar Republic must be understood in the socioeconomic context, including the economic disturbances, inflation, difficulties of international trade, and the Great Depression, surrounding Germany during the 1920s and the early 1930s (Kocka 1988, 4). The institutional defect of the Weimar Constitution, especially the provision of emergency powers for the federal president, also enabled Hitler’s rise (Bernhard 2005, 66). However, the contribution of the anti-democratic forces in the state, protected in the name of democracy, to the demise of the first German republic should not be overlooked.

The Weimar Republic ignored warnings that a constitution could not be a suicide pact, and rejected arguments that any system, however democratic, must protect itself against enemies seeking to use its safeguards and democratic institutions to destroy the system itself. Consequently, the republic fell victim to a bureaucracy and a judiciary indifferent or hostile to republican principles (Showalter 1983, 101). The Weimar Constitution was based on the belief that the composition of the parliament should reflect as accurately as possible the various social interest groups that constituted the nation, while the notion that “parliament was also responsible for creating viable governmental majorities receded into the background” (Mommsen 1989, 56). The Weimar Republic failed to maintain a “viable institutional balance between loyalty to a system and freedom of opinion” (Showalter 1983, 102).

The Weimar Republic case illustrates that disaffected groups with increasing support can challenge the most fundamental values of liberal democracies. The designers of the Weimar Constitution and the political leaders of the new republic failed to realize that the liberal state should not concede the political space to those who wished to use it to destroy the space itself (Dyzenhaus 1997, 121). The tragic aspect of Weimar Germany was that the state institutions themselves became a political space through the process of politicization of the bureaucrats and judges.

The strong bureaucracy and the independent judiciary that had become dominant social forces in Weimar Germany continued to have an antidemocratic or anti-republican ethos. Their stance, along with a decline in the reliability and policy responsiveness of the bureaucracy and the different speeds at which the political realm and bureaucracy democratized, had a deleterious effect on democracy in Germany. The democratically overspeeding and weak regime could not withstand competition from the democratically sluggish and strong bureaucracy and independent court.

The government of the Weimar Republic, which abruptly replaced the authoritarian empire after Germany’s defeat in the 1914–18 war, was characterized by variations in the “speed and rhythm” of movement of its different parts (Frank 1966, 737). This discrepancy created the dilemma of how to incorporate and coordinate the mutually antipathetic and unsynchronized institutional components of the state. The political element aimed to determine policies for democratization and provide the leadership with the means to execute them; the bureaucratic and judicial elements tended to protect the vested interests of traditional groups and the ideological orientation of the previous administrative and legal procedures. In the context of such uneven levels of democratization, the constitution itself became a powerful force against democratization.The case of Weimar Germany illustrates that not only the strength (efficiency and cohesiveness) but also the ethos (ethics and ideology) of the bureaucracy is crucial in the process of democratization. As the German case shows, a strong bureaucracy imbued with an anti-democratic ethos is as threatening to democracy as an internally dismantled, weak bureaucracy that cannot provide efficiency and stability in a democratic regime. A modern democracy cannot exist without a relatively powerful and independent bureaucracy that does not need to mobilize electoral support for itself or its party (Etzioni-Halevy 1983, 87). However, a strong bureaucracy can be either a stepping stone to democracy or a stumbling block against democratic transition, depending on the ethos of the bureaucracy. It should be asked, then, what factors determine the strength and ethos of the bureaucracy, and the answer must be found in the political and social contexts surrounding the bureaucracy. The bureaucracy, its power, and its ethos should be examined in consideration of the bureaucracy’s relationships with political power and the dominant social forces.In the German case, the strong bureaucracy embedded in the dominant social forces in the previous authoritarian regime continued to have an anti-democratic or anti-republican ethos in the new democratic regime. The bureaucrats’ antipathy to the democratic regime, their reduced reliability and policy responsiveness, and the inconsistency between the speeds of democratization of the political realm and the bureaucracy negatively affected the fate of democracy in Weimar Germany. While the parliamentary system and electoral institutions democratized too quickly, other institutions within the state (i.e., the judiciary and the bureaucracy) trailed behind as a result of lingering anti-democratic forces. The democratically overshooting and weak regime could not survive on the back of the democratically sluggish and strong bureaucracy. The democratic constitution of the Weimar Republic protected rather than constrained these anti-democratic forces, thus leading to a failure to protect the democratic polity.

- CONCLUSION

- Countries that experience the abrupt collapse of an authoritarian regime face difficult challenges in the initiation and consolidation of democracy, unlike advanced democratic countries that have benefited from long-term, structural social changes and the natural emergence of democratic forces. Newly democratic countries tend to experience variable speeds and sequences of democratization among the different institutional bodies. While parliamentary institutions or elected bodies tend to speed toward democratization, administrative bodies, the police, and the judiciary may lag. When such institutions are staffed by anti-democratic and anti-republican forces whose interests are embedded in an old political, social, and economic system, the uneven degrees of democratization can cause the erosion, and even the collapse, of democracy.

Democratic constitutions and laws can establish new rules that coordinate conflicting institutional bodies, and independent judiciaries can resolve institutional conflicts within the state. However, as the case of Weimar Germany illustrates, a democratic constitution that guarantees the political and civil rights of the bureaucracy and the independence of the judiciary from political intervention can hinder rather than promote democratization. By providing political and civil rights to anti-democratic forces within the state and perpetuating the embeddedness of bureaucrats and judiciaries in specific social forces or classes, democratic constitutions of this sort can subvert their very purpose.

This study does not argue that democratic constitutions always or essentially work against democratization. Without democratic constitutional rules and legal frameworks, democracy cannot be viable. Instead, this study discussed the initial period of democratic transition after the abrupt collapse of an authoritarian regime and the anti-democratic and anti-republican forces that may gain ascendancy within state institutions during these periods. In the specific conditions of the Weimar Republic, a democratic constitution and judicial independence gave rise to a paradoxical situation in which democracy itself permitted the development of anti-democratic sentiment and action, and the institutions of the state advanced at different speeds and in different directions. Moreover, this study does not argue that a democratic constitution should not be promulgated in the initial period following the demise of authoritarian rule. Instead, a democratic regime must protect itself against enemies within the state seeking to use the safeguards of the constitution to destroy the system itself.

The case of Weimar Germany constitutes a valuable lesson for the new democracies in Eastern Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia about how the self-defense of democracy against internal threats is critical to the successful transition from a nascent, unstable democracy into a consolidated democracy. Many new democracies are experiencing democratic backsliding, either incrementally or rapidly, after the foundation of electoral democracy. Even countries that have been called the most successful examples of new democracies, such as South Korea, are not immune to democratic decay. The Weimar Republic teaches us that political democratization itself is not so omnipotent as to cause automatic democratization of state institutions. For the consolidation of democracy, state institutions (including the bureaucracy, judiciary, and law enforcement agencies), which had been imbued with and become accustomed to authoritarian ethos, mentality, and practices, should be reformed through the elimination of all remnants of authoritarian traits.

However, the example of Weimar Germany should not lead to the other extreme: an emphasis on militant or even illiberal means of protecting democracy. This could also endanger the democracy itself by restraining and oppressing democratic values in the name of democratic self-defense. Any imbalance on either side (values of democracy or means of defending democracy) could lead to a crisis in the democracy or the authoritarian backlash against democracy. New democracies should maintain balance between values and means by reforming state institutions through legal and consensusbased measures, such as the introduction of transparent recruitment and promotion systems, retraining of state officials, intensification of accountability of bureaucrats to citizens and parliament, and reinforcement of civil society’s monitoring of the state, rather than through overly militant and illiberal means.

- Tables

- Table. 1. Uneven Democratization in the State

- Table. 2. The Political Affiliation of the Landräte in Prussia in 1930

- References

-

- Baker, Randall. 2002. “Transition and Reform in Post-Authoritarian States.” In Randall Baker ed., Transition from Authoritarianism: The Role of the Bureaucracy . Westport: Praeger.

- Barabashev, Alexei, et al. 2009. “The Fate of Russian Officialdom: Fundamental Reform or Technical Improvements?” In Don K. Rowney and Eugene Huskey eds., Russian Bureaucracy and the State: Officialdom from Alexander III to Vladimir Putin . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bermeo, Nancy. 2016. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27(1), 5-19.

- Bernhard, Michael. 2005. Institutions and the Fate of Democracy: Germany and Poland in the Twentieth Century . Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Blachly, Frederick F., and Miriam E. Oatman. 1928. The Government and Administration of Germany . Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.

- Bookbinder, Paul. 1996. Weimar Germany: The Republic of the Reasonable . Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Browder, George C. 1996. Hitler’s Enforcers: The Gestapo and the SS Security Service in the Nazi Revolution . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Caplan, Jane. 1988. Government Without Administration: State and Civil Service in Weimar and Nazi Germany . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chu, Yun-han, and Hyug Baeg Im. 2013. “The Two Turnovers in South Korea and Taiwan.” In Larry Diamond, Marc F. Plattner, and Yun-han Chu eds., Democracy in East Asia: A New Century . Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Dyzenhaus, David. 1997. “Legal Theory in the Collapse of Weimar: Contemporary Lessons?” The American Political Science Review 91(1), 121-134.

- Etzioni-Halevy, Eva. 1983. Bureaucracy and Democracy: A Political Dilemma . London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Fish, M. Steven. 2001. “The Dynamics of Democratic Erosion.” In Richard D. Anderson, Jr., M. Steven Fish, Stephen Hanson, and Philip G. Roeder eds., Postcommunism and the Theory of Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Frank, Elke. 1966. “The role of Bureaucracy in Transition.” The Journal of Politics 28(4), 725-753.

- Fried, Hans Ernest. 1943. “German Militarism: Substitute for Revolution.” Political Science Quarterly 58(4), 481-513.

- Geyer, Michael. 1981. “Professionals and Junkers: German Rearmament and Politics in the Weimar Republic.” In Richard Bessel and E.J. Feuchtwanger eds., Social Change and Political Development in Weimar Germany . Totowa, New Jersey: Barnes and Noble Books.

- Ginsburg, Tom. 2003. Judicial Review in New Democracies: Constitutional Courts in Asian Cases . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Glees, Anthony. 1974. “Albert C. Grzesinski and the Politics of Prussia, 1926- 1930.” The English Historical Review 89(353), 814-834.

- Hanson, Stephen E. 2001. “Defining Democratic Consolidation.” In Richard D. Anderson, Jr., M. Steven Fish, Stephen Hanson, and Philip G. Roeder eds., Postcommunism and the Theory of Democracy . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hirschl, Ran. 2008. “The Judicialization of Mega-Politics and the Rise of Political Courts.” Annual Review of Political Science 11, 93-118.

- Heiber, Helmut. 1993. The Weimar Republic . Oxford: Blackwell.

- Helmke, Gretchen, and Frances Rosenbluth. 2009. “Regimes and the Rule of Law: Judicial Independence in Comparative Perspective.” Annual Review of Political Science 12, 345-66.

- Huntington, Samuel. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies . New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Jacob, Herbert. 1963. German Administration Since Bismarck: Central Authority Versus Local Autonomy . New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Kirshner, Alexander S. 2014. A Theory of Militant Democracy: The Ethics of Combatting Political Extremism . New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Kocka, Jurgen. 1988. “German History before Hitler: The Debate about the German Sonderweg.” Journal of Contemporary History 23(1), 3-16.

- Linz, Juan J., Alfred Stepan. 1996. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe . Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University press.

- Magaloni, Beatriz. 2008. “Enforcing the Autocratic Political Order and the Rule of Courts: The Case of Mexico.” In Tom Ginsburg and Tamir Moustafa eds., Rule by Law: The Politics of Courts in Authoritarian Regimes . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Malkopoulou, Anthoula, and Ludvig Norman. 2018. “Three Models of Democratic Self-Defence: Militant Democracy and Its Alternatives.” Political Studies 66(2), 442-458.

- Marx, Fritz Morstein. 1934. “German Bureaucracy in Transition.” The American Political Science Review 28(3), 467-480.

- Mommsen, Hans. 1996. The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy . Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

- Moore, Jr., Barrington. 1966. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World . Boston: Beacon Press.

- Moustafa, Tamir. 2003. “Law versus the State: The Judicialization of Politics in Egypt.” Law & Social Inquiry 28(4), 883-930.

- Muncy, Lysbeth W. 1947. “The Junkers and the Prussian Administration from 1918 to 1939.” The Review of Politics 9(4), 482-501.

- Muncy, Lysbeth W. 1970. The Junker: In the Prussian Administration Under William II, 1888-1914 . New York: Howard Fertig.

- Orlow, Dietrich. 1986. Weimar Prussia 1918-1925: The Unlikely Rock of Democracy . Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Peerenboom, Randall. 2004. “Varieties of Rule of Law: An Introduction and Provisional Conclusion.” In Randall Peerenboom ed., Asian Discourses of Rule of law: Theories and Implementation of Rule of Law in Twelve Asian Countries, France and the U.S . London: Routledge.

- Peters, B. Guy and Jon Pierre. 2004. “Politicization of the Civil Service: Concepts, Causes, Consequences.” In B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre eds., Politicization of the Civil Service in Comparative Perspective: The Quest for Control . New York: Routledge.

- Reinke, Herbert. 1997. “Policing Politics in Germany from Weimar to the Stasi.” In Mark Mazower ed., The Policing of Politics in the Twentieth Century: Historical Perspectives . Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Rohl, J.C.G. 1967. “Higher Civil Servants in Germany, 1890-1900.” Journal of Contemporary History 2(3), 101-121.

- Rosenberg, Hans. 1958. Bureaucracy, Aristocracy and Autocracy: The Prussian Experience 1660-1815 . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Rosenberg, Hans. 1985. “The Pseudo-Democratisation of the Junker Class.” In Georg Iggers ed., The Social History of Politics: Critical Perspectives in West German Historical Writing Since 1945 . Heidelberg: Berg.

- Seabury, Paul. 1954. The Wilhelmstrasse: A Study of German Diplomats Under the Nazi Regime . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Showalter, Dennis. 1983. “The Politics of Bureaucracy in the Weimar Republic: The Case of Julius Streicher.” German Studies Review 6(1), 101-118.

- Suleiman, Ezra. 1999. “Bureaucracy and Democratic Consolidation: Lessons from Eastern Europe.” In Lisa Anderson ed., Transition to Democracy . New York: Columbia University Press.

- Thompson, E. P. 1975. Whigs and Hunters: The Origin of the Black Act . London: Breviary Stuff Publications.

- Tiede, Lydia Brashear. 2006. “Judicial Independence: Often Cited, Rarely Understood.” Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 15 , 130-161.

- Tracey, Donald R. 1972. “Reform in the Early Weimar Republic: The Thuringian Example.” The Journal of Modern History 44(2), 195-212.

- Varol, Ozan O. 2015. “Stealth Authoritarianism.” Iowa Law Review 100(4), 1676-1715.

- Vierhaus, Rudolf. 1999. “The Prussian Bureaucracy Reconsidered.” In John Brewer and Eckhart Hellmuth eds., Rethinking Leviathan: The Eighteenth-Century State in Britain and Germany . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, Graham K. 1993. “Counter Elites and Bureaucracies.” Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration 6(3), 426-437.

- Witt, Peter-Christian. 1985. “The Prussian Landrat as Tax Official, 1891-1918.” In Georg Iggers ed., The Social History of Politics: Critical Perspectives in West German Historical Writing Since 1945 . Heidelberg: Berg.

- Woods, Patricia J. 2009. “The Ideational Foundations of Israel’s ‘Constitutional Revolution’.” Political Research Quarterly 62(4), 811-824.

-